by Evi Mibelli.

“The straight line is without God.”

If many think that the very Milanese and renowned ‘Bosco verticale’ represents the most ambitious idea of contemporary green architecture on urban soil, they will have to think again. Because knowing architecture also means knowing how to look back. At least fifty years back. There are those who wanted to call themselves the Vegetation Wizard. It was Friedensreich Hundertwasser, the artist-architect who left behind unique, unexpected and astonishing works. And he deserves to be recalled periodically for having supported the importance of the integration between plant life, architecture and living. A pioneer of green architecture and an ecologically focused worldview that intertwines diverse fields: from food to agriculture, from mobility to landscape, from design to construction.

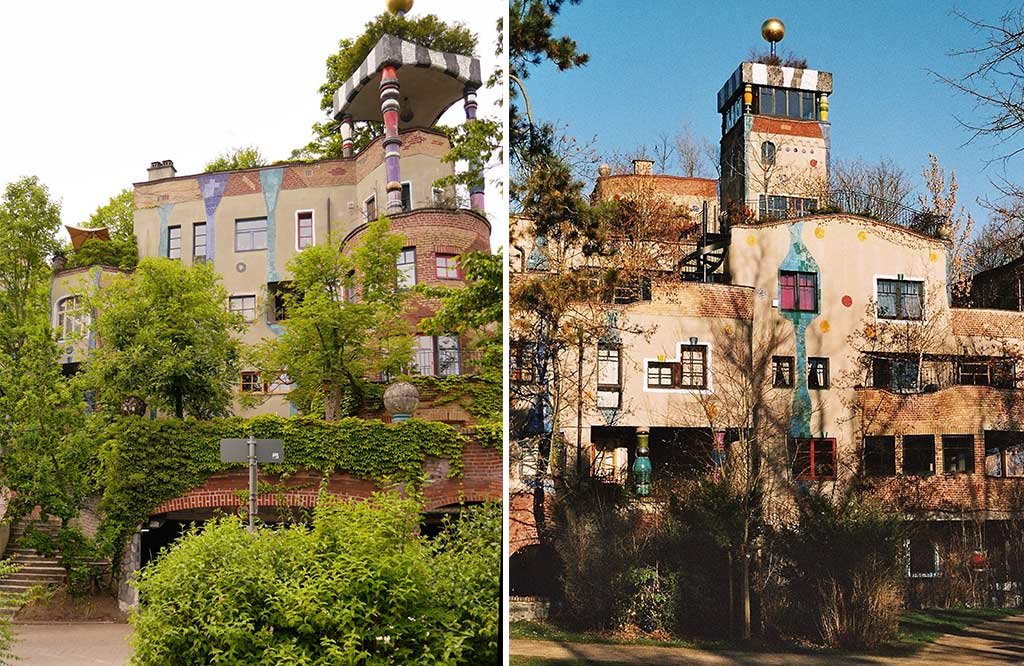

Waldspirale building complex – literally Forest Spiral, consisting of 105 apartments – built in 1998 in Darmstadt, Germany. Photo Jorge Franganillo

He was born on December 15, 1928 in Vienna. As a teenager he began to develop a remarkable pictorial ability and was especially attracted by natural subjects and the beauty of countryside landscapes. Despite the climate of great violence – we are in the midst of wartime and the risk of roundups is extremely high since his mother is of Jewish origins (his grandmother and aunt were deported and later killed in a concentration camp) – his pictorial subjects are serene, pacified by the contemplation of Nature. After finishing high school, in 1948 he enrolled at the Wiener Akademie Der Künste in Vienna.

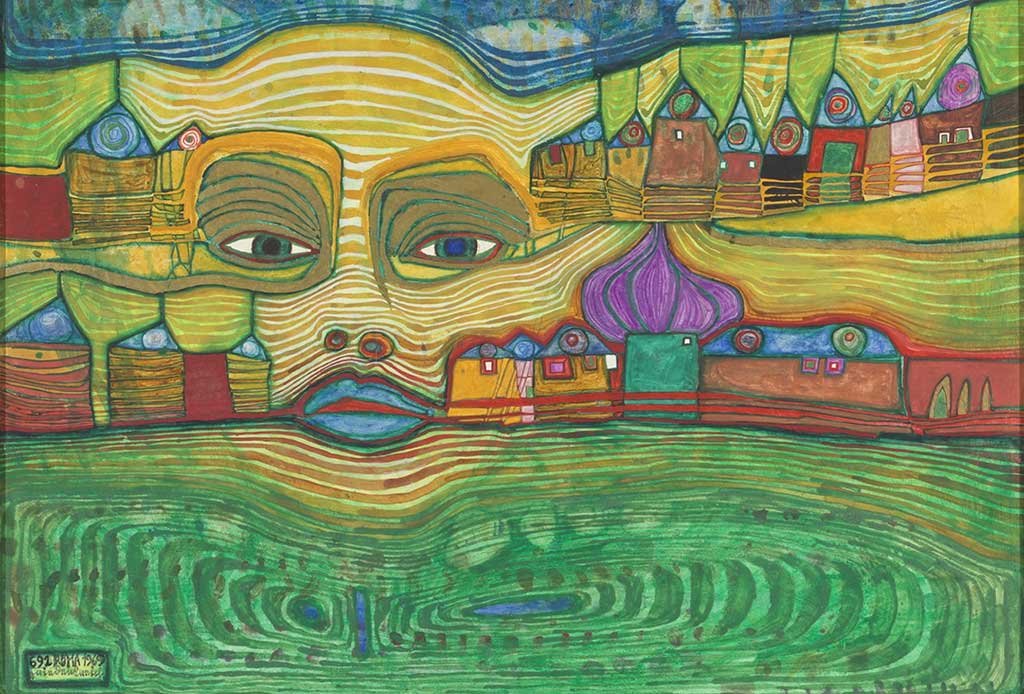

“Irinaland over the Balkans”, limited edition work on silk in 31 colours, printed by Dietz Offzin, Lengmoos, Bayern, 1971.

But he will soon abandon it, finding no stimuli for his volcanic creativity. He developed, as a self-taught artist, an original figurative style in which he masterfully integrated various sources of inspiration, starting with Walter Kaufmann, Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Wassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall and Paul Klee, whose traits we will also find in his architecture.

The post-war years saw him travel and establish himself as a painter, with solo exhibitions in Austria, Germany, France and later in Japan and New Zealand. His language veers towards the decorative and symbolic abstract, resorting to evocative geometries such as the spiral as an allusion to creativity and life. A recurring element in his vast artistic production. As well as the use of bright, shiny, metallic and natural colors.

Main facade of the Hundertwasserhaus, Vienna, 1985. Photo Jorge Franganillo

But let’s get to his idea of architecture. From the early 1960s onward, he declared war on rationalism, and he did so from afar, invoking the Austrian architect Adolf Loos, the proto-rationalist who published the pamphlet “Ornament and Crime” in 1908.

He wrote: “I attack these houses, horrible boxes that look like prisons. Loos exalted straight lines,uniformity, smooth surfaces. Now we have smooth surfaces everywhere. On smooth surfaces, everything slides; even God falls. The straight line is theonly sterile line. While I understand his good intentions, he has literally poisoned the future of architecture in our century.”

To this idea of construction—which would find its ultimate expression in the Bauhaus and post-war functionalism—he would attribute the decline toward standardization, individualism, lack of creativity, and the alienation experienced by contemporary man. A very clear position, leaving no room for interpretation.

And he explains the reason for his aversion: “The criminal laws that repress free and creative architecture must be repealed. People still don’t know that it is their right to decide the appearance of both the clothes they wear and the homes they inhabit, inside and out. Theindividual has a particular right to his own architectural epidermis, on one condition: his neighbors and the stability of the building must not suffer. The home, this third skin of man, should evolve, change, transform; hindering this process is as criminal as hindering the growth and development of a child. This is exactly what we see happening all the time in architecture, and my work aims to counter this situation.”

Residential complex in Bad Soden am Taunus, Germany, 1993. Photo GFHund, Dietmar Giljohann

Observing his architecture, everything becomes clear. Nature is not expressed through orthogonality but through organic, soft, and fluid forms. His avowed dislike of symmetry is underscored by his habit of strictly wearing mismatched socks. There is a need for freedom and wonder. Certainly, almost sixty years later, his words sound revolutionary. Especially now that we find ourselves in a world where bureaucracy and regulations stifle any desire for constructive rebellion.

The Green Citadel in Magdeburg, Germany. View from Cathedral Square. Construction completed in 2005. Photo Axel Tschentscher

In recent times, we have witnessed the development of technologies capable of integrating plant elements into built environments. In this sense, Hundertwasser demonstrated his openness to the use of technology, but only as a tool to foster a free vision of living spaces and built environments: “The technologies for planting lawns, woods, gardens, and trees on buildings are now so advanced that there is no longer any excuse for not having a roof garden.”

He was so ahead of the curve in contemporary architecture that, as early as 1973, he created the installation “The Tenant Tree” as part of the Milan Triennale, planting 15 trees on the buildings on Via Manzoni. “The Tenant Tree represents a turning point, in which thetree is once again given an important role as a partner to humanity. The relationship between man and vegetation must take on religious dimensions. Only if you love thetree as yourself will you survive. […] The sterile, vertical walls that delimit the space between houses, whose tyranny andaggression we suffer every day, are transformed into green valleys where man can breathe freely.”

Read today, it seems like a sad paradox when considering the current rampant Italian mania for cutting down trees in cities. His vision is echoed in the architecture that various municipalities—Vienna, Darmstadt, Magdeburg—have courageously approved and built. His Hundertwasserhaus, the architectural complex located at Kegelgasse 34-38, in Vienna’s 3rd district, is particularly famous.

Left, detail of the ceramic columns. Hundertwasserhaus, Vienna, 1985. Photo JKB; right, detail of one of the entrances to the Hundertwasserhaus, Vienna, 1985.

Built between 1983 and 1986, it is a true prototype of social housing, consisting of 50 apartments with shops, restaurants, and bars, a children’s playground, a gym, 16 private terraces, and three shared areas. It is an entirely public project (meaning that there are courageous municipalities investing in significant projects). The City of Vienna still manages the complex and rents it at controlled prices, favoring families with contemporary artists.

Clay bricks for the walls, wood for the doors and windows, ceramic for the floors, non-toxic glues and paints: the Hundertwasserhaus was consistently built with eco-friendly materials. Energy-efficient too: triple-glazed windows have been installed, and hot water is produced by heat pumps.

And what about the tenant trees? They grow forests on the complex’s terraces and roofs, irrigated by rainwater collection tanks. Green roofs are constructed using root-blocking sheets, insulating panels, and layers of pumice and gravel to ensure drainage and protect the floors. Hundertwasser went further by also designing a biological wastewater recovery system that exploits the purifying properties of certain plants, redistributing nutrients back to the soil.

Overview of the hanging gardens of the Hundertwasserhaus, Vienna, 1985. Photo Paasikivi

But the amazement comes from observing the facades, walking on uneven floors, touching the curved walls and the varied construction materials with your hands. It’s an absolutely unique sensory experience because “in nature nothing is straight.” The apartments are distinguished, on the outside, by the different colors of the facades, by the windows no two alike (the equivalent of eyes, for Hundertwasser), by the bizarre ceramic columns that open onto entrance halls and terraces. An unusual absence of edges is noticeable.

Dettaglio su una finestra e sulla composizione materica della facciata del complesso Waldspirale a Darmstadt, Germania. Photo Immanel Giel

His poetics is disruptive and draws on something archaic and natural. His need to know and move transforms him into a messenger of bioarchitecture, conceived as closer to nature than to reason. Viaggerà a bordo di una imbarcazione restaurata – la Regentag – che lo condurrà in molti paesi. He will go as far as New Zealand where he will purchase the Kaurinui Valley with the aim of returning the land to nature. He planted more than 100,000 native trees, built canals, ponds and wetlands to promote biodiversity.

The Spittelau incinerator, Vienna, 1992. Photo Dimitry Anikin

A separate note should be dedicated to the recovery of the Spittelau incinerator, commissioned by the municipality of Vienna, destroyed by fire in 1987. Hundertwasser transformed it from an industrial building into a monumental work of art, visible from every corner of the Austrian capital. Inaugurated in 1992, the incinerator transforms energy from household waste into heat for over 60,000 families each year. This is the reason why Hundertwasser accepted the commission, otherwise the incinerator represented, in his eyes, the symbol of what destroys nature. Throughout the 1990s he continued to work on numerous projects in Japan, Germany, Austria and New Zealand, alongside teaching at major European academies, particularly the one in Vienna, his hometown.

Hundertwasser died of a heart attack on February 19, 2000, aboard the Queen Elisabeth 2, during a voyage in the Pacific Ocean. He was buried in New Zealand as per his wishes, in the Garden of the Happy Dead, under a tulip tree. There is no gravestone, but that’s not surprising. He wrote in 1979: “I look forward to becoming humus myself, buried without a coffin under a tree on my land at Ao Tea Roa” (New Zealand). A poetic and poignant return to where it all begins.

Left, tower of the Kuchlbauer brewery in Abensberg, Germany. Photo Heribert Pohl; on the right, the toilette of the Kuchlbauer brewery, in Abensberg, Germany. Photo Kora27

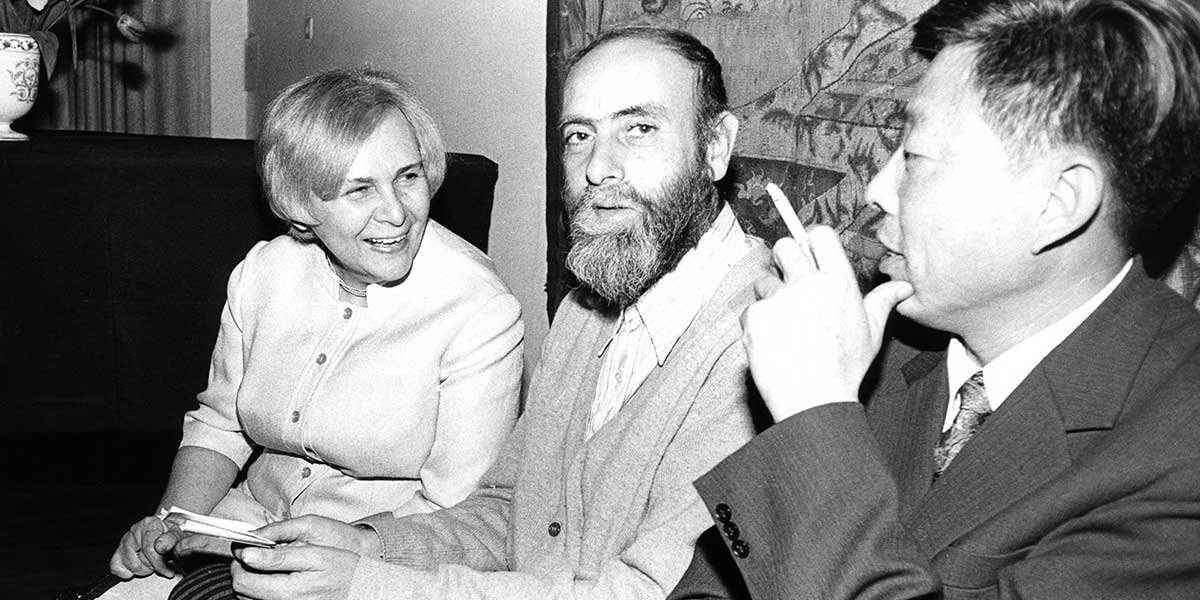

On the cover, Friedensreich Hundertwasser, during an exhibition at the Ewa Kuryluk Art Gallery, 1975. Photo Archive Ewa Kuryluk.