Born on May 18, 1883, in Berlin, Walter Gropius is considered one of the greatest pioneers of modern architecture of the 20th century and is primarily remembered as the founder of the Bauhaus, along with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Alvar Aalto, and Frank Lloyd Wright. The son of an architect, Gropius himself decided to study architecture in Munich and Berlin, and in 1907 he began working in the office of Peter Behrens, one of the first architects to implement the stylistic features of the modern movement, who at the time was working on projects for the AEG company.

Here he met Adolf Meyer with whom in 1910 he opened a studio in Berlin where he remained until the beginning of the First World War. Together they designed the Fagus shoe mold factory, an absolute novelty in the field of workplace architecture with its three floors of large steel-framed windows that made the entire building light and elegant, contrasting with the austere image of the traditional factory.

For the first time, self-supporting, all-glass facades and corners are used on a multi-story masonry building, a choice that also has the symbolic value of offering a glimpse of the factory work, displayed with dignity. The Fagus workshops were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2011 as a symbol of the success of 20th-century industrial culture.

Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer, Officine Fagus, Germany, 1907-1910

The project reflects Gropius’s considerations of the modern factory, which was to assume a leading role in the development of a new culture where the industrialist became a sort of intellectual and artistic patron. The factory was no longer seen as an unhealthy and uncomfortable place, but as a symbol of the collaboration between architect and entrepreneur that led to improved quality and productivity throughout the entire supply chain.

Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer, Officine Fagus, Germany, 1907-1910

After the Great War, he committed himself to reforming art education and in 1919 in Weimar he combined the School of Applied Arts and the Higher Institute of Fine Arts into a single institute nicknamed Bauhaus, the most influential school of art and design in history that completely overturned the canons of many artistic disciplines and gave birth to a language that still influences the world of contemporary design today.

Art and craft, theory and practice were to be unified into a total work of art. Students collaborate in researching modern and innovative uses of industrial materials and in creating mass-produced furniture, taught by personalities such as Paul Klee, Johannes Itten, Josef Albers, Herbet Bayer, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Wassily Kandinsky.

Gropius’s office at the Bauhaus in Weimar, 1923, photo Fabrice Fouillet.

The architect takes care of the interiors by designing the desk, armchair, sofa and ceiling lamps.

Axonometric project of the office

Walter Gropius, F51 sofa and armchair, Tecta, 1920

The shapes are rigorous and the lines are clear. The structure with cantilevered armrests and a backrest that does not touch the ground marks an important step that prefigures the creations of Marcel Breuer’s cantilever chairs of 1925.

On the left, Walter Gropius, F51 armchair, Tecta, 1920. On the right, Walter Gropius, D51 armchair, Tecta, 1922

With the rise of Nazi ideology in 1925, the Bauhaus moved to Dessau and Gropius designed its new headquarters, considered an absolute masterpiece of modern architecture that best embodies the main canons of Rationalism.

The floor plan and spaces are designed solely for their intended use: a block for classrooms, a second block for laboratories, and a bridge connecting the two blocks, intended for administrative offices, the library, and the director’s office.

The external structure is made of reinforced concrete covered with white plaster, the large ribbon windows are made of glass with steel frames and all the interior furnishings are designed by the students according to the school’s principles and created in the laboratories.

Walter Gropius, complesso del Bauhaus, Dessau,1925, ph. Oskar Da Riz

Walter Gropius, Bauhaus complex, Dessau, 1925

Walter Gropius, Bauhaus complex, Dessau, 1925

In 1928 he left the direction of the school, which tried in vain to survive National Socialism until its final closure in 1933. He subsequently practiced privately and his research focused on the theme of modern housing and collective living with the design of various neighborhoods such as Siemensstadt in Berlin.

Walter Gropius, Siemensstadt district, Berlin, 1925, PH. Wolfgang Bittne

In 1934 he left Germany, where anti-Semitism was rampant, and took refuge first in England and in 1937 in the United States, where he taught at Harvard‘s Graduate School of Design and headed the architecture department until 1952. At the same time, from 1938 to 1941 he ran an architectural studio together with his colleague Marcel Breuer and in 1946 he founded the TAC (The Architects Collaborative), a working group of young American architects with whom he signed his post-war works.

The final phase of his career saw the construction of several buildings such as the Hansaviertel residential complex for the 1957 International Architecture Exhibition, the Gropiusstadt district in Berlin named after him, and the Bauhaus archive, designed in 1964 but only built in 1979.

Left, Walter Gropius, Hansaviertel district, Berlin, 1957. On the right, Walter Gropius, Gropisstadt district, Berlin, 1960, ph. Yannick Selinger

Walter Gropius died in Boston in 1969, and his contribution to modern architecture remains invaluable. Rationalism would not have existed without his theoretical reflections and teaching experience, in which all architectural disciplines, from design to urban planning, found a precise functional place.

Walter Gropius and TAC (The Architects Collaborative) Tac Service, Rosenthal, 1969

Porcelain service in which the circle and the sphere are the main formal elements.

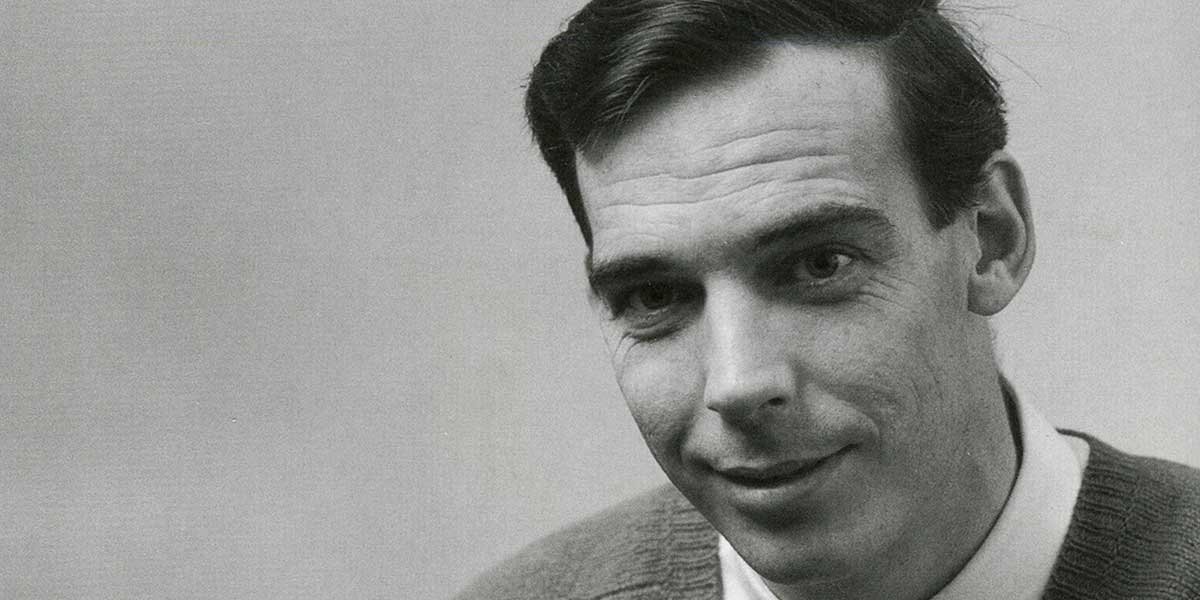

In the cover image, Walter Gropius, ph Getty Images